Home - Kikkoman x The Rembrandt House Museum

The Kikkoman factory in the Netherlands has been supporting the Rembrandt House Museum for over 25 years now. This was because of the special bond Rembrandt had with Japan.

“For many people it is a surprise to hear of Rembrandt’s love for Japan, but for anyone visiting the Rembrandt House, it is quickly clear how many connections there were. Kikkoman is a highly valued partner, for whom craftsmanship is a core value: they help us in turn make Rembrandt’s craftmanship accessible for everyone.”

Milou Halbesma

General Director

Rembrandt the artist was also a voracious collector. This passion grew out of his curiosity about the world around him—close at hand and far away. The neighbourhood he lived in was a melting pot of people from around the world, many of whom were economic, religious or political fugitives who had found a safe haven in Amsterdam. All around him Rembrandt had access to a diversity of people and cultures. His own extensive art collection— which he built up throughout his life—also played an important role. As far as we know, Rembrandt never travelled to other countries. Instead, he brought the world to him by buying large numbers of shells, pieces of coral and stuffed animals, as well as art objects and utensils from distant lands and cultures.

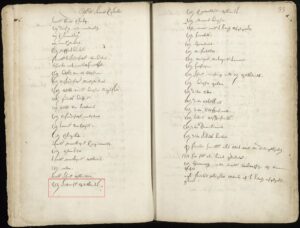

We know that Rembrandt had a large collection of rarities and art objects because in the summer of 1656 he had to have a record made of everything he owned. This inventory was carried out as part of the proceedings for the bankruptcy that he was facing. For two days, an official from the town hall accompanied the artist through the house in Breestraat, and together they made a list of the objects there. Like the rest of the house, the ‘art cabinet’ was systematically inventoried. This room was on the first floor at the back of the house. It is clear from the list of its contents — which is still held in the Amsterdam City Archives — that Rembrandt had set out this large room in his imposing house as a sort of museum. It was an impressive place to take friends and guests. But its overriding purpose was to provide him with inspiration for his own work.

Since 1999, the Rembrandt House Museum has restored, refitted and refurnished Rembrandt’s former home on the basis of the inventory and other sources. The art cabinet, like the painter’s studio, is one of the most appealing rooms. Every effort has been made to give the fullest possible idea of Rembrandt’s collection (fig. 1). However, one specific object with a fascinating story was conspicuous by its absence: ‘een Japanse hellemet’, as it is described in the inventory, was missing (fig. 2). No longer, though, because the museum has been able to purchase one and this helmet is now part of the permanent display.

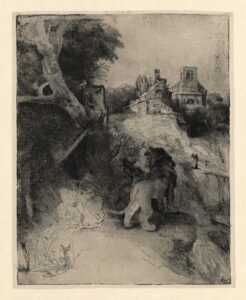

Finding an appropriate piece called for a degree of detective work. Japanese helmets come in numerous shapes and sizes. In this case, however, as well as the listing in the inventory, we had another source to go by—a visual image of Rembrandt’s helmet. When we turn a Rembrandt drawing of an Old Testament murder scene through forty-five degrees, we see a swift sketch of a Japanese helmet (figs. 3a and b). On stylistic grounds, the drawing is dated to around the time of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy. Rembrandt probably jotted down the shape of his helmet on this compositional drawing in haste, before he had to part with this unusual object.

Bas Verberk (curator of the Japanese collection in the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst in Cologne) recognized the helmet in the sketch as a kabuto of the zunari type. This was a relatively easily made type of helmet that was worn in fights by samurai (Japanese warriors), chiefly in the sixteenth century. Luc Taelman, collector and President of the Western Branch of the Japanese Armor Society, proved to

own a suitable early seventeenth-century example that he was prepared to sell to the museum (fig. 4). The object bears a strong resemblance to the helmet Rembrandt must have had. On the side of the helmet in his little sketch Rembrandt drew a fastening point for an ornament. This detail —which seldom occurs on helmets, exclusively on such old examples — can also be seen on this helmet.

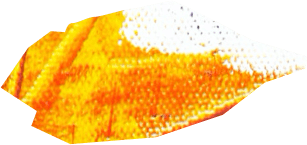

This purchase enables the museum to display an unusual element in Rembrandt’s collection to the public. But the significance of this helmet goes beyond the object itself, for Rembrandt was also interested in other products from Japan. In 1647 he started to use Japanese paper extensively in printing his etchings. He had evidently managed to get his hands on a quantity of sheets of gampi paper. This special paper — yellowish in tone with a sheen — gave the prints a particularly artistic and exclusive character (figs. 5a and b). The impressions printed on Japanese paper (washi) must have been regarded as ‘exotic’, de luxe editions. It is clear that in Rembrandt’s eyes, too, the paper gave the prints a special quality, because he printed a little etched portrait of his son Titus—a precious image that was probably only ever owned by Rembrandt’s nearest and dearest—exclusively on gampi paper.

But there is more. Among Rembrandt’s early clients and collectors was a highly placed official of the Dutch East India Company, who had served in Japan. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Jacques Specx (1585-1652) had been one of the founders of the Dutch trading post in Hirado (Kyūshū, Japan). He had travelled through the country to visit the shogūn, Japan’s military ruler, and even had a daughter with a Japanese woman. In the years when Specx was in contact with Rembrandt, he bought some important history pieces from the artist. He also commissioned him to paint marriage portraits of his sister-in-law Petronella Buys and her husband Philips Lucasz. In the same years, Rembrandt incorporated a fully outfitted Japanese warrior in one of his narrative paintings (fig. 6). Might he have seen a complete samurai costume like this on a visit to Specx’s home? And did he acquire his own kabuto through a contact of this kind.

Rembrandt could also have bought his helmet from one of the Asian shops in and around Amsterdam’s Warmoesstraat. They stocked items brought to Amsterdam through the Dutch East India Company’s expansion operations. Goods from the occupied territories were often looted. The conditions in which the Dutch Republic did business with Japan, however, were of a different nature. The Company was the only foreign trading organization with the official right, granted by the Japanese shogūn, to trade with and from Japan. To this end, the Dutch foreigners had to settle under strict conditions on the artificial island of Deshima, off the coast of the port of Nagasaki. As a general rule, the Dutch were not allowed to leave the island except for an annual visit to the capital, Edo. And the goods they exported from Japan were strictly supervised by the Japanese authorities.

Perhaps Rembrandt also bought a Japanese gift for his second love, Hendrickje Stoffels, from one of these shops. In the second half of the seventeenth century, typical Japanese house coats— banyans — influenced by the kimonos brought back by the Company, became very popular in the Netherlands. Thick, winter versions were specially made for the market for the half-frozen Dutch. An informal portrait of Hendrickje, actually a lighting study, that Rembrandt painted around 1659 shows her in one of these winter gowns (fig. 7). She has pushed her hands into the wide sleeves to keep warm. It is true that no such garment appears on the bankruptcy inventory that had been drawn up a few years earlier, but her possessions were not included in the sales of Rembrandt’s goods and were consequently

neither recorded nor sold.

Finally, there is also an indication that Rembrandt owned Japanese weapons. Playwright Andries Pels claimed in his Use and Abuse of the Scene (1681) about Rembrandt that he ‘door de ganscha Stad op bruggen, en op hoeken, / Op Nieuwe, en Noordermarkt zeer yv’rig op ging zoeken / Harnassen, Moriljons, Japonsche Ponjerts [Japanse zwaarden], bont, / En rafelkraagen, die hy schilderachtig vond’. For this reason, there is also a Japanese katana sword in the arrangement of the artificial caemer, near the Japanese helmet.

After more than three and a half centuries, Rembrandt has a Japanese helmet again. This acquisition lets the Rembrandt House explore and explain more stories behind his work and life, and the time and context in which Rembrandt lived and worked in Amsterdam. The museum already held important examples of prints that Rembrandt printed on Japanese paper, but their sensitivity to light means that they can only be shown once every few years. This makes the acquisition of this helmet a valuable enrichment of the permanent display.

Toegankelijkheid gereedschappen